By Giorgio Brosio, Juan Pablo Jiemenez and Ignacio Ruelas[1]

Decarbonization and its fiscal implications

This short text aims at exploring the fiscal, more precisely the revenue impact, between and within countries, coming from changing trends of the production and use of natural resources deriving from decarbonization and energy transition policies. For illustrative purposes, it will refer to the case of some Latin America countries. The region is emerging as a leading producer of minerals demanded by decarbonization. At the same time, it is also a primary producer of fossil fuels. These circumstances produce winners and losers at the national level. There are also winners and losers at the subnational level since most Latin American countries share natural resource revenues between the central and the subnational levels of government.

Our work is based on a few political assumptions and some technological, economic, and fiscal facts, subject to variation over time. Assumptions refer to the commitment that countries took at COP21 held in 2015 in Paris to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels and ideally to 1.5°C to avert catastrophic outcomes. COP28 held in late 2023 in Dubai confirmed this commitment, engaging countries to curb the production and use of fossils, although with several loopholes. It implies cutting greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible, with the remaining emissions captured.

Achieving final targets requires, from the technological point of view, shifting from the simple addition of new sources of energy to the full substitution of fossil fuels i.e. enacting an energy transition. In turn, investment in clean renewable energies and their use requires expanded production of critical minerals.

The final targets can be achieved with a combination of regulatory policies; granting of subsidies and public investments (all impacting on public expenditure); markets for trade of emissions and issuing of emissions permits; and finally of tax instruments, such as carbon taxes and specific taxes on fuels. There is a large space for substitution and complementing these policies. Our focus is quite narrow, but critical for producers of natural resources since it looks at the final impact of these policies and reactions to them by firms and individuals on their public revenues.

These revenues and their variation reach critical dimensions in countries specialized in the production (and use) of fossil fuels, minerals and “rare earths” required by the decarbonization process. These are called critical because of actual or possible future imbalances between demand and supply.

Short analysis of the revenue impact and its risks

The revenue impact of decarbonization (and the consequent energy transition) is the net result of two opposite trends. The first one is positive and consists of the collections of taxes (or other instruments for extracting rents) levied on the production of critical minerals and rare earths. The second one is expected to be negative starting from the moment when countries experiment with a reduction of the production and consumption of fossil fuels because of a decline in demand following their policies.

Fiscal revenues from natural resources, including fossil fuels, are levied at two distinct stages, upstream and downstream. Upstream revenues, usually called royalties are collected at the moment of the production of the resource, be it the mouth of the well or the mine (or the port of export, when the resource is entirely sold abroad). The total revenue depends on the tax rate, the quantity sold, the price of the natural resources that is determined on the international market, and, very importantly, on the cost of production. The cost varies greatly among countries and determines the net rent, i.e., the base for levying taxes. More importantly, the cost determines when, in the case of critical minerals, a country will be able to enter the market (the price must be higher than the cost), or, in the case of fossil fuels, it will be forced to leave it (the cost becomes higher than the price).

|

Table 1. Oil extraction marginal cost. 2016 |

|||

|

Country |

Exploration Type |

Marginal Cost |

Transportation |

|

Russia |

Arctic |

120 |

NA |

|

Onshore |

18 |

12 |

|

|

Europe |

Biodiesel |

110 |

2 |

|

Ethanol |

103 |

2 |

|

|

Canada |

Sand |

90 |

15 |

|

Brazil |

Ethanol |

66 |

5 |

|

Offshore |

80 |

2 |

|

|

United States |

Deep-water |

57 |

NA |

|

Shale |

73 |

12 |

|

|

Angola |

Offshore |

40 |

NA |

|

Ecuador |

Total |

20 |

NA |

|

Venezuela |

Total |

20 |

NA |

|

Kazakhstan |

Total |

16 |

NA |

|

Nigeria |

Deep-water |

30 |

NA |

|

Onshore |

15 |

NA | |

|

Oman |

Total |

15 |

NA |

|

Qatar |

Total |

15 |

NA |

|

Iran |

Total |

15 |

NA |

|

Algeria |

Total |

15 |

NA |

|

Iraq |

Total |

6 |

NA |

|

Saudi Arabia |

Onshore |

3 |

2 |

|

Source: https://public.knoema.com/tldwcyc/cost-of-oil-production-by-country Table 1 shows the marginal cost of oil production for the main producers. It is immediate to observe that Middle East countries, having the lowest cost will be the latter to abandon production and feel the burden of decarbonization. |

|||

Downstream revenues are collected when the natural resource is used for consumption or production. The specific instrument is excises, i.e. specific taxes usually levied on quantities. Under the current practice worldwide only fossil fuels are subject to specific taxes while the use of minerals is only subject to general sales taxes as every other item.

Downstream taxes on fossil fuels are much higher in the nonproducing countries than in the producing countries. In the latter, low taxes are a way to share directly with the population the benefits derived from the location of the resource within the territory.

Summing up, provided that countries are engaged on the decarbonization path, ie. they proceed to reduce the use of fossil fuels and increase alternative clean sources of energy.

The revenue net impact is as follows: Rn= Gut - Lut + Ldt

Where:

Rn: revenue net impact

Gut: (Potential) gains of revenues from upstream taxes on minerals and rare earths

Lut: Losses of revenue from upstream taxes on fossil minerals

Ldt: losses of revenues from downstream taxes on fossil fuels.

In principle, the quickest way to the disappearance of the use fossil fuels would be to raise the downstream excises on them. The ensuing reduction of demand will produce a corresponding decrease in the production, hence of the international price and, consequently of the producer rent. This implies that consuming countries, most obviously the consuming and non-producing countries could lead the decarbonization process, reducing the tax base for upstream taxes and increasing the tax base for downstream taxes that they could use to their benefit,

Several risks surround the decarbonization process and the ensuing fiscal impact. Countries could delay their exit from fossil fuels and/or proceed with slow speed on the development of alternative sources of energy. There are also risks deriving from the choice of technology, such as an example, those referred to as the so-called «chemistries» in cathode batteries. The resurgence of LFP (lithium-based batteries) and shifting of NMC (nickel, manganese, and cobalt-based batteries) towards chemistries using less cobalt has brought a rapid demand for lithium and a smaller demand for cobalt with an immediate reflection of price and production. A variety of technologies eases concerns about supply but increases uncertainty about the profitability of investments and impact on the country/ local economy and finances leading to fluctuating prices.

A look at the actual dimension of the issues: the samples

We now proceed to the observation of the prospective impact of decarbonization for three distinct samples of cases. The first one is made by fossil fuels heavily dependent countries. The second one includes the largest Latin American countries. The third one looks at subnational governments in Bolivia.

For each of these groups of countries, or of governments, the available information is represented graphically. Figure 1 shows the fossil fuels heavily dependent countries. These countries are ranked according to the dependence of their GDP on rents. As we saw, the rent is the basis on which the taxes can be levied. The degree of dependence reaches astonishing sizes. In more than half of the countries in Figure 2 fossil rents exceed twenty percent of GDP, meaning at least that the abandonment of fossil fuels would require a huge, costly, and risky diversification process of the economy. Since fossil fuels are practically the only source of fiscal revenue, the diversification process would have to be financed by other, new, sources. This explains the strong resistance by these countries to accept a scenario implying the final elimination of the use of fossil fuels.

Happily, decarbonization provides not only losses but also perspectives of gain. These are illustrated in the right-hand side of the figure that reports the potential gains for countries deriving from the availability of critical minerals. Cells filled with an x indicate that the concerned country is among the ten top producers of the listed mineral.

Figure 2. Fossil fuels heavily dependent countries

Sources: Authors’ elaborations from: UNDP (Lars Jensen), Global Decarbonization in Fossil Fuel Export-Dependent Economies.Fiscal and economic transition costs. 2023; U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2023.

Cells marked in blue refer to the minerals most pressing in need.

The right side of the table, the compensation side, has a lot of void cells, meaning that a substantial possibility of compensation is concentrated in very few countries. Some cases are just dramatic. Can we, for example, imagine Iraq without the revenues provided by oil?

Diversification would impact negatively the present standard of life of very dependent countries, making international support necessary, also because wealth sovereign funds, which could finance the transition, are concentrated in very few, rich countries.

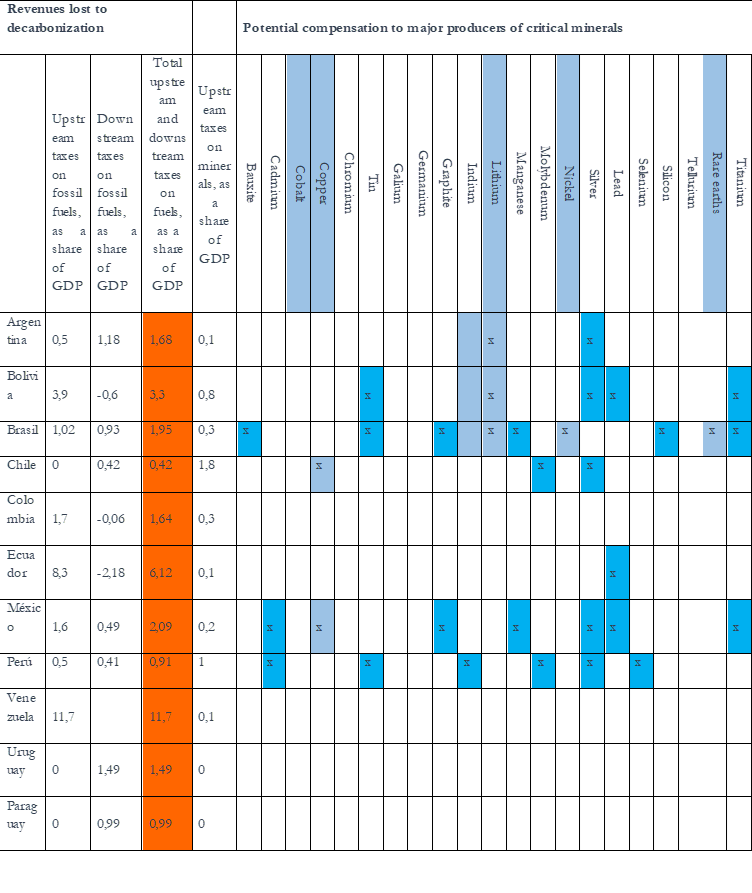

The second, Latin America-focused sample follows in Figure 3. Data is more complete because it includes also downstream taxes that were not available for the first sample. The red column shows the full loss from decarbonization. The table presents a more balanced picture. Only Venezuela is going to lose very substantially. Many countries have large reserves of critical minerals. One of them Bolivia has, as we saw, enormous reserves of lithium.

Figure 3. Prospective losses and potential gains from decarbonization in Latin America

Sources: Authors’ elaborations from: UNDP (Lars Jensen), Global Decarbonization in Fossil Fuel Export-Dependent Economies.

Fiscal and economic transition costs. 2023.; Juan Pablo Jiménez y Andrea Podestá Los recursos fiscales derivados de hidrocarburos y minerales en América Latina. Desafíos ante la imprescindible descarbonización y transición energética. Working Paper 2023; US. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2023.

It provides a good introduction to the subnational impact of decarbonization because present rents from fossil fuels are very spatially concentrated as well as future potential gains. However, there is no correlation between the two cases.

Figure 4. Bolivia. Departments and municipalities

Sources: Authors’ elaborations from: UDAPE Dossier de Estadísticas Sociales y Económicas Volumen 32; Ministerio de mineria y metalurgia. Anuario Estadístico y Situación de la Minería 2022; Población y distribución de recursos fiscales. Desarrollo Sobre la Mesa https://inesad.edu.bo/dslm/2013/07/895/

Figure 4 provides quite detailed information. In addition to upstream and downstream revenue from fossil fuels, it shows also the revenue from upstream taxes on minerals, the mining royalties. This latter revenue would persist in case of decarbonization and would be expanded by the increased demand for critical minerals, specifically lithium. Interestingly, the department of Tarija (the figure has data that pertains to the government of the department aggregated with data about the municipalities included in the area) which is presently the great beneficiary of the oil and gas bonanza will be left with no natural resource revenue. One department, Potosì, would gain enormously from lithium which will add to already substantial mining royalties. Three departments (those in green in the figure) would maintain gains and five departments (those in yellow) would lose mostly from the disappearance of downstream taxes on fossil fuels and will have no gains from the critical minerals.

The Bolivian numbers provide a good case for rethinking the whole issue of the intergovernmental sharing of natural resources revenue. The table provides some relevant information for those readers who would like to start some simulation exercises. The two columns at the right show per capita GDP and population. The distribution of GDP leads to examining the equity issues of the present situation and shows the direction for future changes. Population, especially when coupled with GDP shows the likely cost of compensatory and redistributive measures. Overall, the Bolivian case shows the need of reconsidering the whole system of financing subnational governments with a view to more equity and long term sustainability.

Conclusions

There are no easy conclusions, but to propose that countries concerned with these changes, and also the international community, start elaborating long-term and short-term strategies. Long-term strategies have by definition a time horizon of several decades (generally 10 to 30 years). They are based on assessing the economic size of the natural resources, the evolution of prices, and the effects of longer-term trends with a significant fiscal impact, like decarbonization, demographics, technological change, etc.

A cornerstone of a long-term strategy is economic diversification. Oil and gas-producing countries have a comparative advantage in related sectors, but because of phasing out this diversification is not an option.

Defining a trade-off between the present and the future generations is also crucial, assuming that the present standard of consumption and production are unsustainable. For example, should countries maintain present standards of living, or allow a temporary fall to start diversification? Or should they save in physical capital, according to Hartwick rule, or similar rules, or focus on directing savings to sovereign funds?

Short-term strategies apply also inside single countries, i.e. subnational governments. At this level, they should consider compensation of losers through equalization, or other grants, or assignment/sharing of tax revenues. These policies are feasible but constrained by the erosion of revenues. Changes in the spatial allocation of resource revenues are in principle feasible, but politically arduous.

Compensation between countries is a task for the international community. »Gainers/losers funds», are feasible when targeted to small nations. They become very problematic for large nations, but they are needed.