by Nicoletta Marigo (CNR-IMEM, Parma) and Augusto Ninni (University of Parma and IEFE, Bocconi University, Milano)

Sintesi

Il lavoro analizza il ruolo dei paesi emergenti e di quelli in via di sviluppo nella conferenza COP21 di Parigi (dicembre 2015) in tema di cambiamento climatico, nonché gli impegni precedentemente annunciati dalla Cina e da alcuni paesi ASEAN attraverso gli Intended National Determined Contributions (INDC). L’articolo esamina il pacchetto di interventi previsti dal governo cinese, e sottolinea le differenze e le somiglianze nelle dichiarazioni di intervento dei paesi ASEAN.

Abstract

The paper focuses on the role of emerging and developing countries at the COP21 meeting in Paris (December, 2015) and on the commitments previously provided by China and some ASEAN countries through their Intended National Determined Contributions (INDC). The article assesses the efforts to face climate change disclosed by the Chinese government, and emphasizes the differences and the similarities in the policy declarations of the ASEAN countries.

1.A general picture

At the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) held in Paris in December 2015, 188 countries reached an historic agreement on international action to tackle climate change.

Achievements worth mentioning are:

1) The significance of the commitment. The Parties agreed not only to limit the growth of the world's temperature to the previously set 2° C above pre-industrial levels, but also “to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5° C” (art. 2).

2) The direction of the countries' development. The limits to the temperature increases shall be obtained through net-zero GHG emissions in the second half of the century (art. 4). This opens the way to a deep transformation of the economies1 .

3) The communication of the results. The commitments of the single countries will be analysed through Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC2 ), to be communicated every five years.

4) The importance of resilience. The capacity of the countries to adapt3 to the adverse impacts of climate change will be increased through specific investments.

5) The role of financing. Adequate financial resources must be available to support a climate-resilient and low-carbon economic development.

Despite doubts on the future actual implementation of the Paris agreement4, it succeeded in removing the division between developed and developing countries regarding climate issues. Every country has to assume responsibilities in taking action against climate change, albeit within its capabilities. So the Paris agreement was able to remove the former distinction between Annex-1 and non-Annex-1 countries of the Kyoto Protocol: developed countries are explicitly requested to take the lead in reducing the emissions and in contributing to climate finance (art. 4). Developing (and emerging) countries are instead requested to publish their expected contributions to the fight against climate change and encouraged to give financial support.

Indeed the expected contribution of the emerging countries differs largely: for example, in the BRIC group China and India will reduce their GHG emissions per unit of GDP by 2030 (with respect to 2005), while Brazil and Russia will reduce their GHG emissions in absolute terms, having as reference year 2005 and 1990 respectively.

The existence of these large differences5 suggests to focus the following discussion on China and on other relatively large developing countries, like some ASEAN nations.

2.China

China's commitments to climate change mitigation and adaptation for the post-2020 period includes:

• Peaking CO2 emissions by 2030 if not before.

• Reducing CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by 60-65% from 2005 levels by 2030.

• Increasing non-fossil energy to 20% of its energy consumption by 2030.

What is China doing to achieve these goals and what might be the implications on the country development process? In what follows we focus on few selected and relevant areas.

Phasing out coal. Coal-fired power accounts for 67% of China's total energy consumption and is responsible for three-quarters of the country CO2 emissions. Although coal generation and consumption will stay at high levels in the years to come, economic slow down, industry restructuring and new energy and environmental policies have recently resulted in reduced coal consumption. China is committed to modernize its coal power plants by 2020 and to reduce their pollutant emissions by 60%. This will contribute in saving 100 million tonnes of raw coal and preventing the discharge of about 180 million tonnes of CO2 each year6 .

Bans on new coal power plants are currently in place in three industrial regions and are expected to be extended to a number of other key provinces in 2017. China has also introduced bonuses for plants meeting coal efficiency standards: plants opened after January 2015 will get 0.005 yuan7 per kilowatt hour on top of the basic grid tariff, while those already in operation will get an extra 0.01 yuan per kilowatt hour. The country is complementing these measures with an extensive surveillance system to monitor the compliance level of the numerous power plants spread across the country.

Promoting low carbon energy. China is rapidly becoming a leader in renewable energy production and installations. At the end of 2015 the country was leading the world with 145,104 gigawatt (GW) of cumulative installed wind power and 43 GW of solar photovoltaic, thus overtaking Germany. To further boost adoption of non fossil fuels, China is committed to adopt a clean electricity dispatch system that will prioritize power generation from renewable sources. This is critically important considering that the current electricity system gives priority to coal-fired power plants.

Investments in low carbon energy sources (mainly driven by the Chinese solar industry) have also be considerable reaching US$89.5 billion in 2014 thus exceeding the US and Europe.

Energy efficiency. China’s building stock is characterized by new constructions and large scale urban expansion, both growing rapidly. Buildings account for about one-quarter of China's energy use and the number of new buildings is expected to triple by 2030. China’s energy efficiency effort is therefore prioritising buildings by ensuring that 30% of all new urban buildings will meet by 2020 China's green building standards8 .

In 2014, more than $18 billions were invested in energy efficiency in the Chinese buildings (the majority of which residential), taking the country at the second place in the world energy efficiency investment ranking9 .

Transport. China has the world's second largest vehicle population (after the USA) and the transport sector accounts for 12% of the country CO2 emissions. The country is committed to reach by 2020 a 30% of public transport in urban centres. This will require to slow the growth rate of private transportation by investing in subways, buses and car sharing services. China aims to cut fuel consumption of light commercial vehicles by 20% from 2012 levels by 2020. For this reason the country has been imposing fuel efficiency standards since 200410 .

Implications for the development process. According to a study by Wang Yi 11, done by simulating the effects of several policies on emissions reduction and their effects on the country development, peaking CO2 emissions by 2030 will decrease the GDP by 3.7% to 5.9% under different scenarios and cause a 5.5% to 8.2% reduction in employment. Although controlling emissions (with adjustments in the energy structure and decreases in the energy intensity being among the most important policy measures) and achieving a more sustainable development is of paramount importance for China, the price of the policy mix on the development process will be significant and well above the 1% of the global GDP reckoned necessary by Stern to control the temperature increase by 2°C .

Integrated and comprehensive policy solutions will also be needed for realizing carbon emission peaking. Among these the creation of a carbon trade market will play a key role. China has already established pilot trading systems in seven cities – the first set up occurred in 2011- and intends to establish a national cap and trade system as early as 2017.

3.The large ASEAN countries

As explained before, one of the most important features of the commitments coming from Paris Agreement 2015 was that a country is requested at least to slow down the pace of its GHG emissions, according to its own process of development and the physical features of its territory. A good example of differences among countries in their commitments is provided by some large (Indonesia) and relatively large (Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia) ASEAN countries.

They share at least three important features, which are rather uncommon in Europe:

- They are already well prone to disasters caused mainly by climatic change: according to the Long Term Climatic Risk Index (CRI)12 the highest number of disasters in 1995-2014 was marked by Philippines (337), the highest losses in million US$PPP were marked by Thailand: Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand were respectively the 4th, the 7th and the 9th country in the world in terms of total CRI score.

- In the region the major impacts and risks of climate change are the increased risks of river flooding and sea flooding, leading to damages to infrastructure, livelihoods, and settlements13 , so that adaptation to climate change (resilience) is some times more important than mitigation.

- Changes in the use of land and forests account for an important item of GHG emissions. As these countries committed themselves in their 2015 INDCs to reduce the LULUF14 contribution and to create reforestation efforts, it involves a deep change in their model of development, previously strongly based on the exploitation of natural resources (mainly in Indonesia and Malaysia).

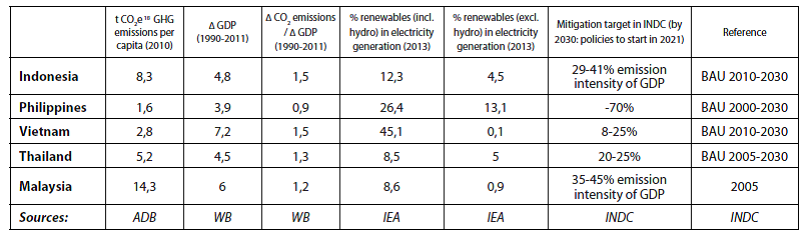

Considering the mitigation policy (Table 1), these countries commit themselves to reduce their own emissions even without receiving technological or financial help from abroad (first percentage of the second to last column)15 in 2030 with reference to the Business As Usual (BAU) scenario. It means they do not commit to reduce the absolute amount of the emissions, but only the growth rate16 . Furthermore, among the analysed countries only Vietnam explicitly claims to face climate change in a pro-active way, by developing a domestic renewable energy equipment industry, even if the incidence of renewables (excluding hydro) in the electricity generation is rather small in all the countries17 .

Table 1- INDC of large ASEAN countries and their current emission performances.

1 According to Germanwatch, “producers, investors and governments” are now informed that “coal, oil and gas need to be phased-out already in the coming decades” (see H. Breuers and P.M. Richter,“The Paris Climate Agreement: Is It Sufficient to Limit Climate Change?”, DIW Roundup, February 15, 2016).

2 Before the Paris meeting, the countries were requested to provide their Intended National Determined Contributions (INDC), which we will utilize to assess the commitments of China and ASEAN emerging countries. Also in terms of style of language the passage from INDC to NDC means higher level of responsibility for the countries.

3 The Paris agreement underlines the differences between mitigation of the climate change (points 1 and 2) and adaptation to it (point 4).

4 In 2018 the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) will provide an official report about the feasibility of reaching the target.

5 An useful survey of these differences is in M. Davide and P. Vesco, “Assessing the INDCs: a comparison of different approaches”, ICCG Reflection no. 42/December 2015.

6 In 2014 China issued the Energy Development Strategy Action Plan , which targets a 62% coal share in primary energy consumption by 2020.

7 1 yuan = 0.14 €.

8 They will need to satisfy six rating criteria: land, energy, water, resource/material efficiency, indoor environmental quality and operational management.

9 Hua, S. 2015. China seeks energy efficiency in construction. China Daily USA. Available at: http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2015-10/15/content_22195790.htm

10 China is now in Phase IV standard which regulates the fuel consumption of passenger vehicles (both domestically manufactured and imported) for the years 2016 through to 2020. Phases I and II, which ended in 2011, showed successful reduction of 11.5% in average fuel consumption and related emissions.

11 Wang, Y. and Zou, L. 2014. The economic impact of emission peaking control policies and China's sustainable development. Advances in Climate Change Research 5: 162-168.

12 Germanwatch: CRI is an average of death toll, death per 100.000 inhabitants, total losses in million US$PPP, losses for unit GDP%, number of events (total 1995-2014).

13 Asian Development Bank, “Southeast Asia and the economics of global climate stabilization”, 2015.

14 Land use, land-use change and forestry.

15 Of course the committed reduction is larger if this help from abroad is obtained (see the second percentage number).

16 For example according to Vietnam’s INDC, the expected million t CO2e emitted in 2030 shall be 787.4 according to the BAU scenario (a 219% increase with respect to 2010). Vietnam commits itself to increase its emissions in 2030 by 193% with own resources, by 139 % if helped by other countries.

17 Geothermal is important in Philippines and Indonesia, biofuels in Thailand.

18 CO2 equivalent.

Newsletter N. 03 | MAY 2016 - Scarica il pdf