Jeanne Vallette d'Osia - Thesis abstract, Master in Development Economics (University of Göttingen and University of Clermont-Auvergne)

Abstract:

Especially in low and middle-income countries, the level of women’s empowerment, which is “the expansion in people’s ability to make strategic life choices in a context where this ability was previously denied to them” (Kabeer, 1999), has a strong impact on family size. In turn, the degree of women’s property rights (PR), such as their legal access to property, land and inheritance compared to that of men’s, has a strong impact on their total empowerment. What are the mechanisms linking women’s PR to their fertility behaviors[1]? They appear to be mostly related to the increase at the household level in bargaining power women benefit from their access to asset ownership. The trade-off between ownership and fertility is highly related to the social and institutional environment in which women live. Overall, realized fertility rates decrease as far as women obtain more access to property and inheritance rights. On the contrary, due to families’ preference for male offspring in some countries, an increase of female decisional power at the household level can lead to a higher number of children.

Introduction:

The 5th Sustainable Development Goal adopted by the United Nations - “achieve gender equality and empower all women and and girls”[2]- is a core objective in human rights’ fight, but it is also fundamental in order to achieve long-term development outcomes.

Indeed, among the biggest obstacles preventing women from exercising their rights to property and inheritance there are pervasive discriminatory social attitudes and behaviors, which have been proven to lead to a decrease in gender equality and economic inefficiencies[3] . Morrison et al. (2007) illustrate the idea that reaching a state where access to rights and opportunities are independent of gender allows for a more sustainable and resilient development path, obtained through productivity gains and more inclusive institutions and policy choices.

The gender gap in economic well-being, social status, and empowerment is mostly explained by the gender gap in access to resources derived from land ownership (Chakrabarti, 2017). Mainly in developing countries, and specifically in rural areas, women often take care of the family’s assets while being denied the access to property and inheritance rights (United Nations, 1994). In rural India, less than 10% of women possess legal titles to land even though 70% of the agricultural active labor force is female (Bose and Das, 2020).

Women also face an additional burden in terms of their standard of living, which is manifested in the existence of a fertility gap, with the fertility gap being “the difference between the number of children women would like to have (fertility intentions) and the (final) fertility rate”.[4]As one of the main driver of demographic fluctuations, the decision of having children and the actual realization of doing so have strong implications for development, making reproductive rights (such as the number and spacing of children) human rights (United Nations, 2013).

Regarding reproductive decisions at the family level, Eguavoen et al. (2007) observed that for 65% of their 684 randomly selected households in Nigeria, “the man stands out as the traditional head of the home and therefore the decision maker including reproductive decisions.” (p°46). It is clear here that if women’s intrahousehold status would be improved, they would have more voice regarding decisions on family matters, such as the use of contraception or, for instance, the number or spacing of children.

Interlinkages:

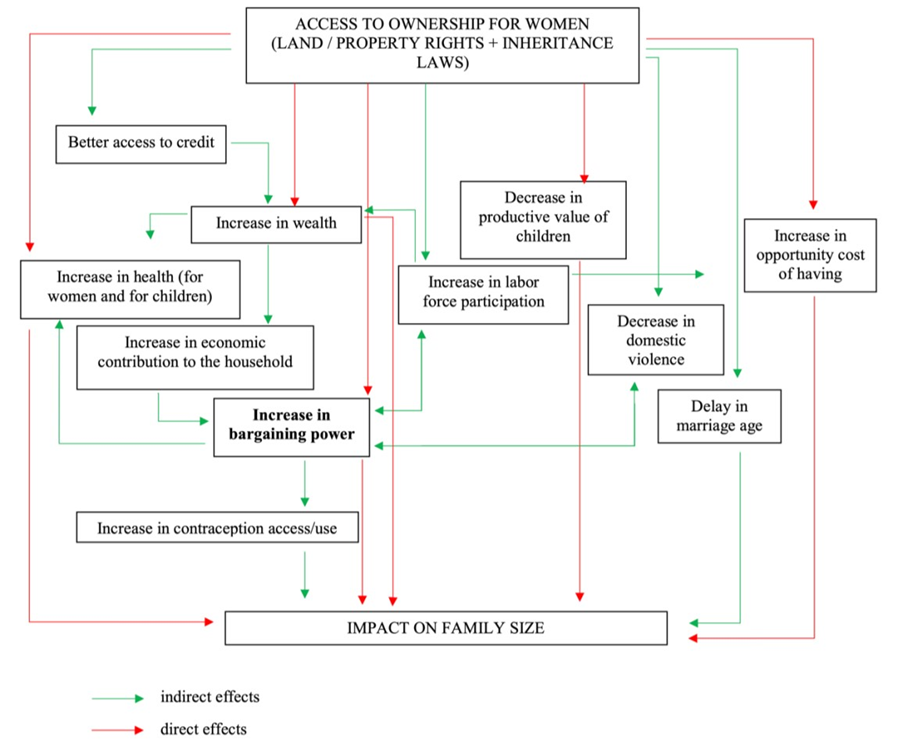

The conceptual framework summarizing the links between female land ownership and family size is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Conceptual Framework

As the decision about family size is made at the close family level, the lack of woman’s access to the position of head of the household is one of the main gender discriminations that prevents them from getting their desired number of children.

Firstly, thank to empowering processes, women can change their behaviors as regards family planning. The ownership of tangible assets gives women more independence, a sense of security (both physical and psychological) (Campus, 2016), and the opportunity to recover from shocks (Chakrabarti, 2017). There is a wide range of literature showing that legal recognition of women’s PR is favorable to women’s household bargaining power[5]. Additionally, several dimensions are affected by a better access to PR which in turn increase household decisionmaking: evolution of the marriage market[6] with a delay in the age of marriage and childbearing (Harari, 2019), reduction of domestic violence (Oduro et al., 2015,), or higher economic contribution to the household (Melesse et al., 2017).

Then, the increased bargaining power of women within their home tends to increase women’s agency in their reproductive preferences. Women can better shape their own desires and have more power in fulfilling them. The costs related to pregnancy, weaning newborns and raising children are mainly borne by women rather than men. In this perspective, entitling women to apply their preferences regarding their desired and actual number of children through an increase in their decision-making leads to a reduction in family size (Eswaran, 2002). Additionally, the indirect effects of education (Afoakwah et al., 2020), access and uses of contraception (Biswas and Kabir, 2002) and better management of household health expenses (Schmidt, 2012) might increase women’s bargaining power regarding family planning.

An increase in female PR might influence fertility in different ways: first, the female wealth promoted by PR might increase thank to income that women obtained from farming, renting, or selling their land, and through access to credit in order to invest and start remunerative activities. Land ownership is also related to access to subsidies, training, and other economic supports that tend to make women wealthier (Dekker, 2013; Chakrabarti, 2017).

Then, there is a reduction of gender discrimination and an increase in labor force participation, not only in the agriculture sector, but also in wage labor (Hallward-Driemeier et al., 2013). Moreover, the access to land rights tends to reduce the productive value of children as securing women’s PR affects the level of home production compared to the market one, and also tends to reduce the role assigned to children of securing informal tenure rights or providing old-age subsistence (Field, 2003). Finally, because women will probably allocate more time to work following an increase in their PR, the opportunity cost of having children will rise and therefore impact fertility rates (Field, 2003).

The literature agrees on the fact that all those mechanisms are negatively linked to fertility behaviors, with an increase in female PR leading to a decrease in desired and actual number of children. This result only arises if the assumption that children are perceived as normal goods holds. Indeed, in such a case, women increase resource allocation towards children to improve their overall well-being, following a trade-off between the quantity and quality of children. Besides this assumption, Doepke and Tertilt (2018) stated that a shift to a more equal PR system between men and women in developing countries would lead to a fall in the overall fertility rate. However, this assumption does not hold with children perceived as investment goods that provide old-age subsistence and be a way for parents to secure tenure rights. For instance, in the specific context of son preference, (which is prevalent in India[7]or in Nepal[8]due to economic, religious, and social traditional patterns), women tend to use their increased bargaining power not to reduce the childbirth, but to get the desired number of sons. The reproductive choices of women are then subject to the stopping rule, which is the mother’s ability to reach her desired number of sons according to the gender of her previous children (Bose and Das, 2020). Gudbrandsen (2013) well illustrated this phenomenon by showing that in Nepal, female autonomy was leading families with daughters as first child to have more children even though the overall fertility rate decreased.

All these processes are however subject to failure, with cases where the expected effects of PR and legacy interventions may not be realized. First, PR only do not always translate into effective control over returns on assets as the effectiveness of PR’ interventions is influenced by other factors, such as the perceived tenure security or shifts in social conflicts (Lawry et al. 2017). Additionally, it might be the case that the expansion of female PR should happen along with access to other productive resources, technologies, and advisory services to support the economic empowerment they would enhance (Campus, 2016). In this regard, PR reforms can lead to uncertainty regarding the rights of different users and increase conflict between tenants, use-rights holders, as well as first occupants and their descendants. Corruption and bribery are also obstacles to the effectiveness of land reform (MeinzenDick and Mwangi, 2009). An increase in female ownership rights might even backlash against them regarding intra-household violence, as it might threaten men’s status quo in a family (Dekker, 2013). Moreover, a more equal distribution of PR is not always the key to better access to credit due to the absence of formal credit markets in rural areas, or because alternative ways of accessing credit without land as collateral exist (DFID, 2014).

Another aspect lies in the effectiveness of a legal reform aiming at better gender equality in PR being conditional on the economic situation and judicial system of the country, where countries with a strong rule of law might have a better response to formally recognized rights (Hallward, 2013). Finally, women’s reproductive preferences are conditional on the spheres in which their empowerment occurs. It might be that their intra-household bargaining power is not sufficient by itself and that an increase at the community level is necessary so that the effect on the implementation of women’s desires becomes substantial (Eguavoen et al., 2007).

Results of the systematic review on the topic:

After undertaking a state-of-the art review focusing on the ownership-fertility relationship, it is possible to conclude that the evidence available to assess that female land ownership-fertility relationship is neither relying on unbiased identification strategies nor providing consensual results. The fertility response to changes in women’s access to inheritance and PR is highly dependent on the socio-economic context, as it is what determines whether children are seen as safe investments for the future or normal goods. However, the common trend is that women change their attitude towards pregnancy and childbirth due to the improvement of their bargaining power and the match between their parenthood desires and their possibility to fulfill them. The specific case of India and the son preference’s tendence also highlights the fact that the change in family planning might not be towards the number of children itself, but about the gender of the newborn. Therefore, women’s empowerment through more equal property and inheritance rights might produce demographic changes. Gudbrandsen (2013) observes that if fertility rates drop and son preference persists, which might be the case when studying women’s access to ownership, the gender bias in the population might be magnified with more boys born than girls.

Implications for practice and policy:

Policies aiming at influencing fertility rates and desirable family sizes should highly consider the socio-economic context in which they would be implemented. In order to foresee a demographic change, and maybe reduce fertility gaps, policies should improve the conditions through which property and inheritance rights might give women more autonomy and voice within the household.

More research is needed regarding the female land ownership-fertility relationship as the studies using experimental methods are lacking in the domain. It would also be of great interest to deeply understand the characteristics of women who tend to experience an evolution in their access to PR as it would help both the academic debate and development policies. Finally, future research should try to assess the risk of spillovers between beneficiaries of property rights interventions and non-beneficiaries.

Notes:

[1] This review specifically focus on studies that analyze the evolution of desired fertility rates and realized fertility rates.

[2] Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/

[3] « (…) increases in opportunities for women lead to improvements in human development outcomes, poverty reduction and (…) potentially accelerated economic growth » Morrison et al., 2007, p.4

[4] Source: population-europe.eu

[5] Allendorf, 2007, Beegle et al., 2001, Campus, 2016, Harari, 2019, Mason, 1996, Mishra & Sam, 2016, Quisumbing, 1994.

[6] « refers to the application of economic theory to the analysis of the process that determines how men and women are matched to each other through marriage and how this process influences other choices including human capital investment and the allocation of marital surplus », The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2016.

[7] Bose, N., & Das, S., 2020, Deininger, K., Jin, S., Nagarajan, H. K., & Xia, F., 2019, Tandel, V., Dutta, A., Gandhi, S., & Narayanan, A. 2022.

[8] Chakrabarti, A., 2018.

References:

- Afoakwah, C., Deng, X., & Onur, I. (2020). Women’s Bargaining Power and Children’s Schooling Outcomes: Evidence From Ghana. Feminist Economics, 26(3), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1707847

- Allendorf, K. (2007). Do Women’s Land Rights Promote Empowerment and Child Health in Nepal? World Development, 35(11), 1975–1988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.12.005

- Beegle, K., Frankenberg, E., & Thomas, D. (2001). Bargaining power within couples and use of prenatal and delivery care in Indonesia. Studies in family planning, 32(2), 130-146.

- Biswas, T. K., & Kabir, M. (2002). Women’s Empowerment and Current use of Contraception in Bangladesh. Asia-Pacific Journal of Rural Development, 12(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1018529120020201

- Bose, N., & Das, S. (2020). Women’s Inheritance Rights and Fertility Decisions: Evidence from India. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3783585

- Campus, D. (2016). Does land titling promote women’s empowerment? Evidence from Nepal. Unpublished manuscript, University of Firenze.

- Chakrabarti, A. (2018). Female Land Ownership and Fertility in Nepal. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(9), 1698–1715. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1400017

- Dekker, M. (2013). Promoting Gender Equality and Female Empowerment: A systematic review of the evidence on property rights, labour markets, political participation and violence against women. 129.

- Deininger, K., Jin, S., Nagarajan, H. K., & Xia, F. (2019). Inheritance law reform, empowerment, and human capital accumulation: Second-generation effects from India. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(12), 2549–2571.

- Department for International Development (DFID). (2014). Secure property rights and development: Economic growth and household welfare [Data set]. Koninklijke Brill NV. https://doi.org/10.1163/2210-7975_HRD-9834-2014003

- Doepke, M., & Tertilt, M. (2018). Women’s Empowerment, the Gender Gap in Desired Fertility, and Fertility Outcomes in Developing Countries. 33.

- Eguavoen, A. N. . T., Odiagbe, S. O., & Obetoh, G. I. (2007). The Status of Women, Sex Preference, Decision-Making and Fertility Control in Ekpoma Community of Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences, 15(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2007.11892561

- Eswaran, M. (2002). The empowerment of women, fertility, and child mortality: Towards a theoretical analysis. Journal of Population Economics, 15(3), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001480100070

- Field, E. (2003). Fertility Responses to Land Titling: The Roles of Ownership Security and the Distribution of Household Assets. 41.

- Gudbrandsen, N. H. (2013). Female Autonomy and Fertility in Nepal. South Asia Economic Journal, 14(1), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1391561413477945

- Hallward-Driemeier, M., Hasan, T., & Rusu, A. B. (2013). Women’s Legal Rights over 50 Years: What is the Impact of Reform? The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-6617

- Harari, M. (2019). Women’s Inheritance Rights and Bargaining Power: Evidence from Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 68(1), 189–238. https://doi.org/10.1086/700630

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435-464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

- Lawry, S., Samii, C., Hall, R., Leopold, A., Hornby, D., & Mtero, F. (2017). The impact of land property rights interventions on investment and agricultural productivity in developing countries: A systematic review. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 9(1), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2016.1160947

- Mason, K. O. (1996). Wives' economic decision-making power in the family in five Asian countries (No. 86). East-West Center.

- Meinzen-Dick, R., & Mwangi, E. (2009). Cutting the web of interests: Pitfalls of formalizing property rights. Land Use Policy, 26(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.06.003

- Melesse, M. B., Dabissa, A., & Bulte, E. (2018). Joint Land Certification Programmes and Women’s Empowerment: Evidence from Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(10), 1756–1774. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1327662

- Mishra, K., & Sam, A. G. (2016). Does Women’s Land Ownership Promote Their Empowerment? Empirical Evidence from Nepal. World Development, 78, 360–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.003

- Oduro, A. D., Deere, C. D., & Catanzarite, Z. B. (2015). Women’s Wealth and Intimate Partner Violence: Insights from Ecuador and Ghana. Feminist Economics, 21(2), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2014.997774

- Quisumbing, A. (1994). Improving women’s agricultural productivity as farmers and workers. Education and social policy Department Discussion paper, 37.

- Schmidt, E. M. (2012). The Effect of Women’s Intrahousehold Bargaining Power on Child Health Outcomes in Bangladesh. 29.

- Sinha, N., Raju, D., & Morrison, A. (2007). Gender equality, poverty and economic growth. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (4349)

- Tandel, V., Dutta, A., Gandhi, S., & Narayanan, A. (2022). Women’s Right to Property and the Quantity-Quality Trade-Off of Children: Evidence From India. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4014600